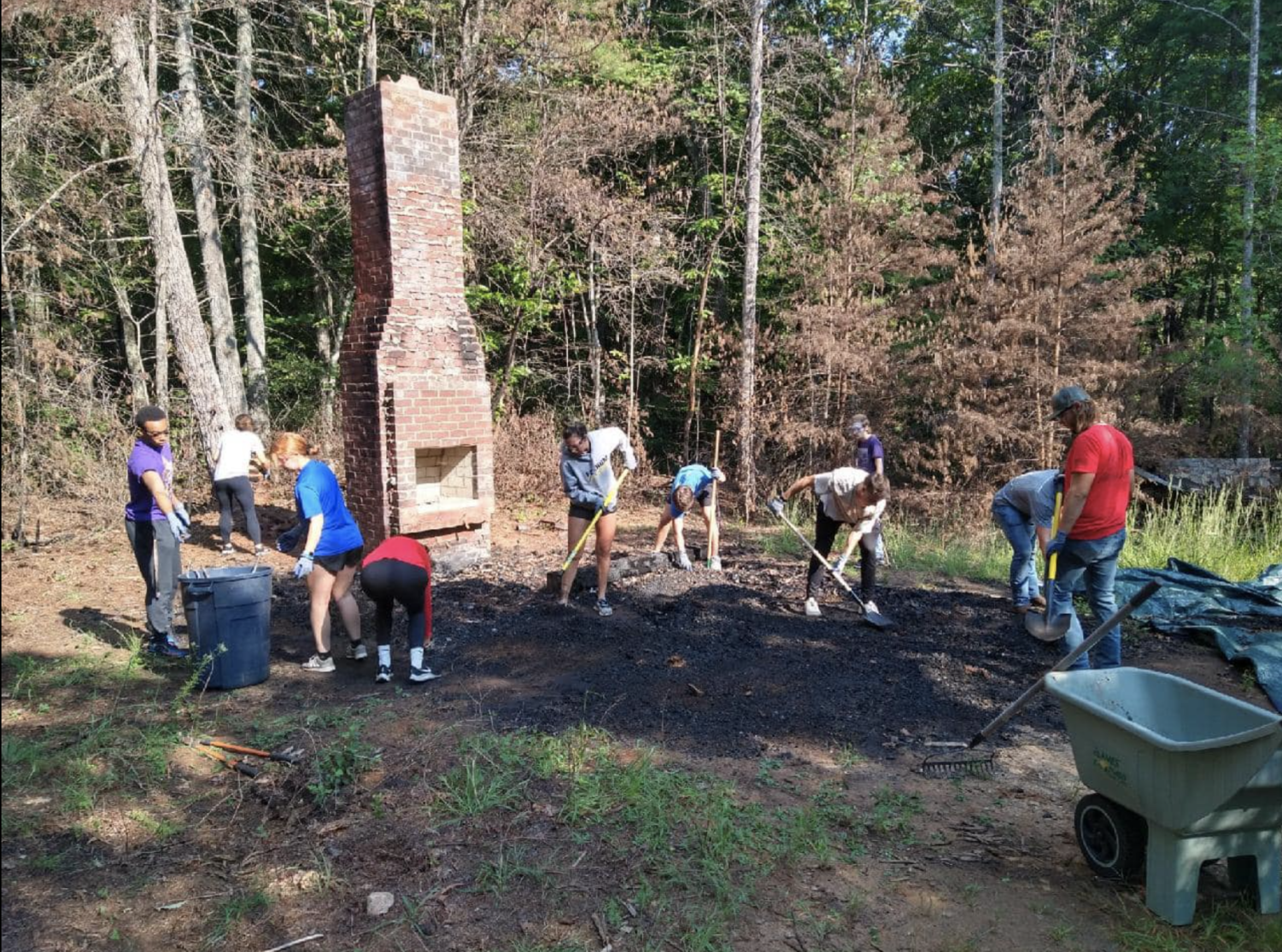

E-Term Remake of Henry David Thoreau’s Cabin Burns

Campus Police Suspect Arson

The replica of the Henry David Thoreau cabin on Waldon Pond burned over the summer. Police suspect arson.

October 4, 2022

A fire began in the woods near campus.

Black smoke spread in the air.

The Ferrum College campus said goodbye to a replica of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin due to suspected arson. Only the chimney remains.

“It was right around 6:20 in the evening on May 20,” said Jim Owens, Chief of Police and Director of Campus Safety.

Sergeant Joseph Kelley and Officer John Acord were on campus when they noticed the black smoke coming from the woods and decided to investigate.

“John got in the car, drove around to wherever the dead-end street is behind the college,” said Owens.

Acord concluded that the smoke was coming from the woods and called the fire department.

“Luckily it didn’t get too out of control as far as the woods around them,” said Owens. “By the time they got to it, the whole thing was fully engulfed.”

Investigating leads to the fire not being an accident.

“It was a pretty day, wasn’t cloudy, so it wasn’t like there were any lightning storms or anything going on, and we certainly don’t have any electricity running up there,” said Owens. “So it leans toward more of it being a man-made type of fire.”

Currently, there are no leads to how the fire started or where it could have originated.

“The fire marshal said that it basically burnt so hot that there was no way of telling where the point of origination was,” said Owens.

The idea to build the cabin began in 2007 in English Professor John Kitterman’s E-Term course 207: American Nature Writers. Kitterman reacted to the burning as a remembrance of Thoreau.

“Thoreau lived in his cabin for two years, two months, and two days,” said Kitterman. “Our cabin got used quite a bit in its 15 years.”

After two years in the making, Thoreau’s cabin was completed in 2009 with the help of merchants and small businesses in the area who donated materials. Students and people in the Ferrum community helped build the close replica.

“Thoreau’s cabin was timber-framed by himself, while ours was stick-built,” said Kitterman. “He had a horsehair plaster interior, and ours was bare wood; he also had a root cellar and an attic ,while ours did not.”

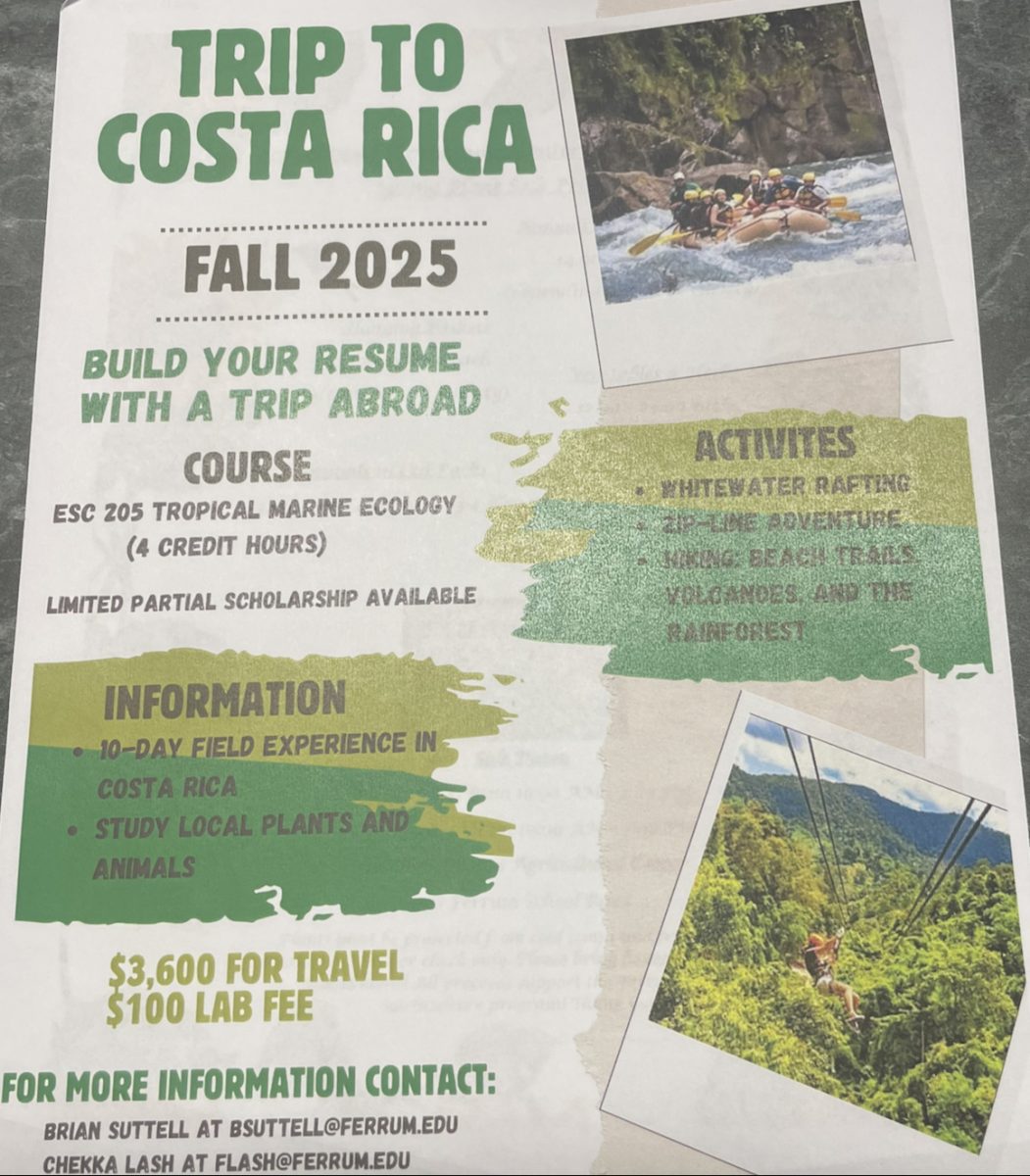

There are no current plans to rebuild the cabin as it would need to be prioritized and up to the college.

“The only way lower priority projects are moved ahead of higher priority projects is if the project has been funded in part or in whole by a donor,” said Barb Hatcher, Vice President for Business and Finance.

If a rebuild were to be done, it would cost the same as it was to build the original.

“To rebuild it today at normal prices would cost about $25,000,” said Kitterman.

Now, Kitterman and Art Professor Jake Smith, plan to clean the debris and place a teepee with Honors 211 students this fall.

“Thoreau was interested in Native Americans and wrote about the ones in New England,” said Kitterman.

Below is the dedication speech Kitterman made in 2010 when the ribbon was cut on the cabin:

One hundred and sixty-five years ago, in the spring of 1845, 27-year-old Henry David Thoreau (pronounced Thorough in his era) borrowed an axe and headed off into the woods outside of Concord, Massachusetts to start building a small one room cabin, ten feet by fifteen feet. He cut his own timbers and shingles from trees surrounding Walden Pond, a kettle pond formed by retreating glaciers and the deepest body of water in Massachusetts, whose waters are crystal clear, cold and pure. By July Henry had completed his snug cabin, finishing the interior walls with horsehair plaster. He moved in on July 4th, Independence Day, and declared his own independence from the world, living self-sufficiently for the next two years, two months, and two days, until his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, who owned the land under his cabin, asked him to come and stay at his home while he was away in Europe. So in September of 1847 Henry Thoreau ended his famous experiment in living.

Henry’s experiment had two objectives. The first, which he described in the opening chapter, called “Economy,” of his book Walden, was to see if a person could live with just the essentials in life, freeing himself from the economy of the world. By building his own home out of natural, second-hand, and salvaged materials Henry managed to spend only 28 dollars, 12 and one-half cents. In today’s currency, that would amount to about 8 or 9 hundred dollars. He kept a garden in the summer and stored much of his produce in his root cellar to eat throughout the rest of the year. The rest of his crops he sold in town to purchase a few necessities like sugar and flour. But he was a vegetarian and did not need much. He also did a few odd jobs as carpenter, mason, or surveyor in the village, and by his own estimate in this fashion he needed to work only about six weeks out of the year to cover all his expenses!

The other reason for his experiment in living in the woods was to free himself from his normal way of thinking. As he put it, he went to the woods to live “deliberately,” that is, consciously and spontaneously, to confront himself every day, to think for himself, instead of living according to the rules of other people. He got many of his ideas from Emerson, who in his essay “Self-Reliance” argued that human beings cannot realize their divine inner nature until they examine who they are in their deepest selves. So Henry plunged into the woods for two years to find his own god in nature, away from the noise of the human world, and the rest is history.

Thoreau is not famous just for his sojourn next to Walden Pond. He would have been a world famous American just for the little essay called “Civil Disobedience,” written after he was jailed for a night for refusing to pay his poll taxes for several years, taxes which supported slavery and an aggressive war against Mexico. This essay, which said that it was right to protest against injustice and disobey the law when the law is unjust, influenced the young Mahatma Gandhi to use a campaign of passive resistance to gain India’s independence from Great Britain, and a decade later convinced a young Martin Luther King, Jr. to use the same tactics to gain civil rights for Blacks in America.

For these reasons, of all Americans who have ever lived, Thoreau was arguably the most influential in the rest of the world. It was because he lived his life in the pursuit of freedom—freedom from mortgages, freedom from government, freedom from spiritual and legal limitations, and freedom is perhaps the greatest thing that America has offered to the world.

That is not to say Henry was not a critic of society. He was, as noted, an abolitionist against the abomination of slavery. He was also very wary of progress, believing that industry and commerce should exist for the good of all mankind, not just for the few. Human beings should be the masters of machines, not the servants, he argued. And of course Henry loved the wildness of nature and strongly believed that it should be preserved for everyone to enjoy and learn from. Among his many other accomplishments, Henry David Thoreau is considered the father of the environmental movement in America. Even today his notes on the plant life around his home are used by climate scientists to understand what has happened to the environment in the last 200 years.

We could not live without Thoreau, and so we teach him in our public schools and colleges and universities around the globe. At Ferrum, in 2007, we started an experiment of our own, creating an experiential term for students to get out of the classroom and learn by doing. The students who started building this cabin were enrolled in English 207, “American Nature Writers.” They read Walden, Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, set in Roanoke, and Thomas Crowe’s Zoro’s Field, set in the North Carolina mountains west of Asheville. The class laid the foundation for the Thoreau cabin replica, raised the walls, and framed the cabin, then we set off for North Carolina to camp and hike and spend a couple of days with Crowe. Then again in 2009 another group of students took another E-term class. This time we finished the interior of the cabin, built a woodshed, and hiked around Mt. Rogers in Virginia. Both courses, I think it is fair to say, took us as far out of the classroom as we could go, carried by the spirit of Henry David.

This cabin is a little different from the original at Walden Pond, which is long gone. For one thing, Chapman Pond is far down the hill, not a hundred feet away. It’s a little bigger than Henry’s, and it’s stick built, not timber framed. It has no root cellar, and no horsehair plaster. But Henry, I believe, would have wanted us to do it our own way, to be independent and self-sufficient. But I went to the community to help us out, and found the people we are publicly thanking today for making this little piece of history possible. The businesses who gave us materials free or at cost: Griffith Lumber Company, Old Virginia Brick, MW Windows (now Ply Gem), Smith Mountain Building Supply, and Lowes. I would also like to thank colleagues and friends who helped with the construction and logistics: Joe Anderson, Jonathan Bier, Charlie Gardner, Jeff Gring, our Provost Leslie Lambert, our President Jennifer Braaten, Andrew Pauley, Rachel Troyer, and Randy Simpson. I want to thank my wife Kathryn for helping me and giving me the freedom to spend countless hours nailing shingles here instead of painting our house. And especially I want to thank Jeff Dalton, without whose expertise and willingness to lend a hand at any time, this cabin would not have been built. I had my doubts that I, who had little carpentry experience, could pull this off, until I met Jeff in the hallway one day his first semester teaching at Ferrum and he told me he was a licensed carpenter. He did a good job. This cabin has been here three and a half years and it’s not going anywhere.

I like to think of it as a time machine. Those F-18 Super Hornet Navy jets that fly so low over the college that one summer day they nearly knocked me off the roof, they are not as fast as this cabin. Just walk through the door and it will transport you back in time 165 years, to the day when Henry David swung an axe over his shoulder and set off to find and free himself.

Thank you for coming and helping to dedicate this cabin in his spirit.

Now let me unveil the plaque, and read it to you, and then I invite everyone to come inside the time machine and have some refreshments.

–John Kitterman