Tears flowed like rivers once educational support navigator Amy Fender’s presentation was complete last Friday.

Crying, laughter, and conversation were served with a side of refreshments during community hour as students and staff alike gathered to learn more about paving the path to education for children with chronic illnesses.

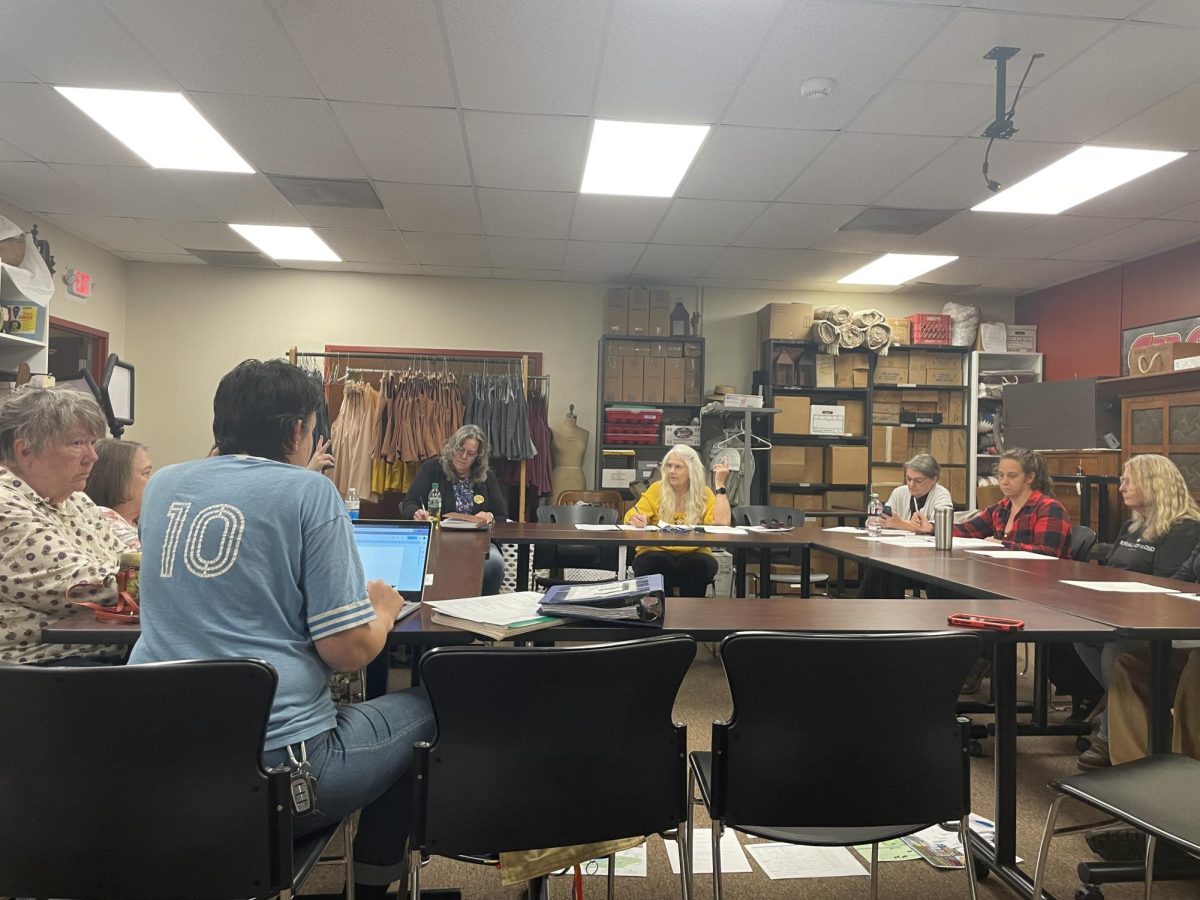

The presentation was sponsored by Kapa Delta Phi (KDP), led by Macey Moore, senior.

“We wanted to offer an educational opportunity to students at Ferrum College,” Moore explained. “This information could be meaningful to their future endeavors, and the effects of childhood cancer are rarely talked about.”

And according to the reactions of the students, the information was meaningful to the audience as well.

Formerly a public-school teacher, Fender is currently an Educational Support Navigator–a professional who serves as a mediator between hospitals and schools to provide the most positive educational experience for children with chronic illness and their families.

However, Fender’s appearance on campus was no coincidence, as she is a former colleague of the college’s Director of Online Learning, Ashley Williams.

“A few weeks ago…Amy reached out,” Williams said. “She asked if she could come and talk to our education students about her position with the ASK Childhood Cancer Foundation at Carilion Children’s Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Clinic in Roanoke.”

Williams was eager to agree.

Finding the subject particularly interesting, KDP seemed just as eager as Williams to take Fender’s arrival on campus as their first event in two years. With approval and three meetings to plan, the group made it happen.

The goal was to encourage education students, along with students of similar majors, to explore future career settings beyond the traditional setting.

Beginning her speech, Fender explained her position. With her office stationed in a hospital, her career is not a common one.

“I have a teaching background,” she offered, “but I no longer teach lessons. I advocate for those with chronic illnesses and bridge the gap between doctors and teachers.”

Fender’s career began upon meeting Associate Director of Education Alma Morgan, who is known for background in advocating for children who are sick.

After an interview, Morgan knew that she had found the right person.

Fender continued to explain that her position is one that has just now come about–15 years ago, it did not exist. Now, Virginia has an education support navigator at six major hospitals in the state.

Her job relates to more than just school, however.

“I took the job to do school things,” Fender said, “but I ended up starting a ‘Friendsgiving’ event. It was a hit. Now we do it once a month instead of once a year.”

These events are more than just a social event–they serve as support, too.

“Families love to meet other families that were facing similar situations,” she commented. “Kids with cancer love to know that there are other kids that understand them. No one fights alone.”

Fender shared that 85% of children with cancer and other chronic illnesses survive, which she explained to be the “why” of her job.

She also noted that of those survivors, two of every three will have at least one late effect of their treatment.

“Building a relationship–that’s the biggest thing,” Fender stated. “There are lots of transition periods to get the kids back to the top. It’s my job to be there every step of the way.”

Fender finished her presentation by sharing stories of advocating for parents who could not explain the diagnosis of their child without tears and encouraging kids returning to school to not be ashamed of the struggles that may come. Williams found this part of the presentation particularly resonating.

“One thing that really resonated with me was that many times the parents are too devastated or emotional to speak during meetings with the school,” she elaborated. “So, the navigator is there to be their voice.”

The real tear-jerker, however, was when she disclosed the reason she pursued this career.

Two of her nephews were born with chronic illnesses that placed limitations on their life. Her first nephew passed away at the age of five, and her second nephew, though having currently fallen ill, was able to complete three weeks of Kindergarten.

“He was only there for a few weeks,” she said with tears welling in her eyes. “But he loved every minute of it. I feel like we sometimes forget how fun school really is for children.”

It would have been hard to walk out of Fender’s presentation without a renewed appreciation for the things that sometimes are taken for granted, such as health or a lack of barriers in early education–nor did many leave with a dry eye.

Concluding her presentation, Fender offered every education major in the room a booklet of classroom accommodations that could help the next generation of teachers provide the best classroom setting for those with childhood cancer and chronic illness. She called it a “toolkit”.

Fender encouraged anyone interested in the field to reach out and pursue it, as well as to volunteer to help make a difference in the lives of small children fighting big battles.